Understanding ConvChain

I’d always wanted to know how videogame designers often make infinite worlds for players to explore, or how rogue-like games such as Diablo create levels.

The technique for creating random patterns is called procedural generation, and my first real introduction to it came, thanks to reddit, through a technique called Wave Function Collapse, created by Maxim Gumin in like 2016.

The algorithm seemed quite simple and I will make its own post soon, however I just couldn’t wrap my head around the implementation. I decided to start with an earlier algorithm of Gumin’s called ConvChain.

The ConvChain algorithm

ConvChain is a Markov chain of images that converges to input-like images. That is, the distribution of NxN patterns in the outputs converges to the distribution of NxN patterns in the input as the process goes on.

At its core, the ConvChain algorithm is itself an implementation of the Metropolis-Hastings algorithm.

The interactive version that I added to the bottom of the page was ported to javascript and optimized with WebGL by Kevin Chapelier. I have made very minimal changes to the algorithm, mainly in how arrays are sorted, as I think there was a mistake in how it’s implemented. It doesn’t actually seem to impact accuracy all that much, though, but I thought I’d leave the changes there.

The Metropolis-Hastings Algorithm

Wikipedia: a Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) method for obtaining a sequence of random samples from a probability distribution from which direct sampling is difficult. New samples are added to the sequence in two steps: first a new sample is proposed based on the previous sample, then the proposed sample is either added to the sequence or rejected depending on the value of the probability distribution at that point.

The Metropolis–Hastings algorithm generates a sequence of sample values in such a way that, as more and more sample values are produced, the distribution of values more closely approximates the desired distribution. These sample values are produced iteratively in such a way, that the distribution of the next sample depends only on the current sample value, which makes the sequence of samples a Markov chain.

The crux of the algorithm goes like this:

- Read the input image and count NxN patterns. (optional) Augment pattern data with rotations and reflections.

- Initialize the image (for example, with independent random values) in some state S0.

- Repeat the Metropolis step: Compute the energy E of the current state S. Choose a random pixel and change its value. Let’s call the resulting state S’. Compute the energy E’ of the state S’. Compare E’ to E. If E’ < E assign the current state to be E’. Otherwise, assign the current state to be E’ with probability

exp(-(E'-E)/T).

S is the current state of any pixel. In his implementation, pixels can be either white or black (0, or 1). Energy is computed via an equation that I will describe later. T stands for temperature, a parameter that can be tweaked to determine how often a value can flip between 0 and 1.

Let’s dive into the code.

Step 0: The Beginning

static bool[,] ConvChain(bool[,] sample, int N, double temperature, int size, int iterations)

{

bool[,] field = new bool[size, size]; // the array of our final output

double[] weights = new double[1 << (N * N)]; //This is where we will store the count of each pattern.

Random random = new Random(); //the magical hat where we draw numbers from

This is the beginning of the main function. We have a boolean 2D array called sample, the size N of the patterns that we will extract from the input image, the temperature parameter that affects how frequently a given pixel flips between 0 and 1, the size of our output image, and the number of iterations the algorithm will run for. Internally, it uses an array named field that will become the final output, and weights, where we will count the amount of times each pattern appears in our input and thus its probability distribution. It then will return a 2D array (bool[,]).

T is for Temperature

Temperature is a variable that we can tweak so that we can directly adjust the probability of a pixel being replaced by a new value. It changes the probability distribution of the state S to p(S) ~ exp(-E(S)/T)

Why 1 « (N * N)?

The expression means “bitwise shift left the number 1 to the left N*N times”. Bitwise shifting left means converting the number to binary, adding zeroes to the right of it and computing the end result. 1, in binary, is 2 to the power of zero, (rock fact: that’s why programmers count from zero) and each zero you tack on to the right adds a power to that 2. So, the code reads “weights is an array of size 2^n*n” in common parlance, but really we’re working with bits here:

Consider an n-sized binary array. It has n*n elements, each 0 or 1. All the combinations possible for the array can fit a binary number with n*n zeros to the right of it, e.g. b10000 for n = 2, or 2^(2*2)=16 in decimal, thus 1 « N*N. We will use weight to count how often often each pattern shows up.

Step 1: Read the input image and count NxN patterns.

…And also augment pattern data with rotations and reflections:

//for each point in the input, get eight patterns

for (int y = 0; y < sample.GetLength(1); y++) for (int x = 0; x < sample.GetLength(0); x++)

{

//The array of Patterns where we'll store them

Pattern[] p = new Pattern[8];

//Get the eight patterns mentioned before.

//No special logic here except for the custom class Pattern which I'll hand-wave away *whoosh*.

//Just take it as the pattern of size N that starts at coords (x,y) in the sample array.

p[0] = new Pattern(sample, x, y, N);

p[1] = p[0].Rotated();

p[2] = p[1].Rotated();

p[3] = p[2].Rotated();

p[4] = p[0].Reflected();

p[5] = p[1].Reflected();

p[6] = p[2].Reflected();

p[7] = p[3].Reflected();

// each transformation of the pattern gets its own count.

// It's my intuition that at the end of the day they all get the same amount of counts.

for (int k = 0; k < 8; k++) weights[p[k].Index()] += 1;

}

//using 0.1 instead of 0 makes it so that an energy state is never 0 *whoosh*.

for (int k = 0; k < weights.Length; k++) if (weights[k] <= 0) weights[k] = 0.1;

We iterate over each pixel in the input, read N pixels ahead and above to make an NxN array (the algorithm wraps around the image if there aren’t enough pixels), rotate four times and get the mirror of each pattern (thus getting eight patterns total per pixel). For each pattern created this way, we compute its index in the weights array and increase its count by 1. Finally, all the patterns that weren’t found in this way are set to 0.1 from 0, because we’ll be computing energy states by multiplying counts together and they can’t be non-zero (this will make sense later). The index function is interesting, so I’ll explain that as well:

The Index method

public int Index()

{

int result = 0;

///Size() is just the size of the input array

for (int y = 0; y < Size(); y++) for (int x = 0; x < Size(); x++) result += data[x, y] ? 1 << (y * Size() + x) : 0;

return result;

}

Remember how we calculated the weights array size with bitwise shifting? This method uses the same technique to turn the binary array into a number. Another way to do this would be to just concatenate them as strings, casting them to binary, then to decimal.

Step 2: Initialize the image with independent random values.

This one is trivial: Just fill the array randomly with 1’s and 0’s.

for (int y = 0; y < size; y++) for (int x = 0; x < size; x++) field[x, y] = random.Next(2) == 1;

Step 3: Repeat the Metropolis step

Initialize the metropolis algorithm in a random pixel, and run it enough times so that approximately every pixel in a square image of size size gets iterated on iterations times.

for (int k = 0; k < iterations * size * size; k++) metropolis(random.Next(size), random.Next(size));

The Metropolis-Hastings algorithm

The Metropolis step refers to the Metropolis-Hastings algorithm for getting a random sample out of a probability distribution. From (Wikipedia):

First a new sample is proposed based on the previous sample, then the proposed sample is either added to the sequence or rejected depending on the value of the probability distribution at that point. The resulting sequence can be used to approximate the distribution (e.g. to generate a histogram) or to compute an integral (e.g. an expected value).

In the code it looks like this:

void metropolis(int i, int j)

{

double p = energyExp(i, j); //Calculate the energy state of the given pixel at i,j. This is E in the original description

field[i, j] = !field[i, j]; //flip the bit at i,j

double q = energyExp(i, j); // Re-calculate the energy state of the now-switched pixel at i,j. This is E' in the original description

//If q > p, keep the changes, otherwise randomly revert the changes with P = exp(-(E'-E)/T)

if (Math.Pow(q / p, 1.0 / temperature) < random.NextDouble()) field[i, j] = !field[i, j];

};

If E’(1/p) is smaller than E (1/q), then we keep that bit flipped (assuming temperature is less than 1). Otherwise, flip it back with probability (q/p)^(-t). Let’s talk more about the energy function:

E is for energy

ExUtumno introduces the energy function as E(S) := - sum over all patterns P in S of log(weight(P)) because in the metropolis part of his algorithm he uses exp(-(E'-E)/T). Remember our weight array and how it was used for storing pattern counts? Turns out we actually interpret pattern counts as the log of their probability weight. This describes a log-normal distribution.

The Log-Normal Distribution

A log-normal process is the statistical realization of the multiplicative product of many independent random variables, each of which is positive. This is justified by considering the central limit theorem in the log domain (sometimes called Gibrat’s law). The log-normal distribution is the maximum entropy probability distribution for a random variate X—for which the mean and variance of ln X are specified.

Anyway, here’s the energy function. Hold out your hand, it’s quite cool:

double energyExp(int i, int j)

{

double value = 1.0;

for (int y = j - N + 1; y <= j + N - 1; y++) \

for (int x = i - N + 1; x <= i + N - 1; x++) \

value *= weights[new Pattern(field, x, y, N).Index()];

return value;

};

And how it’s used in the metropolis algorithm:

//If q > p, keep the changes, otherwise randomly revert the changes with P = exp(-(E'-E)/T)

if (Math.Pow(q / p, 1.0 / temperature) < random.NextDouble()) field[i, j] = !field[i, j];

Remember the energy function is the negative sum of the logs of probability weights. Via log properties, this means that the exponential of the energy function will return 1/the product of their counts. When you calculate exp(-(E'-E)/T) you get (q/p)^(1/temperature). when q/p is greater than one and temperature is less than one, you will always keep the bit flipped i.e. move towards a lower entropy state. Otherwise, probability kicks in depending on the magnitude of difference between states, and how “hot” the model is.

So that explains the Metropolis algorithm implementation. We can now return our output image and call it a day

Finally

//the end result

return field;

Don’t forget to like and subscribe! Oh, and don’t forget to check out this interactive version (shoutout again to K. Chapelier).

┳━┳ ヽ(ಠل͜ಠ)ノ

ConvChain GPU example

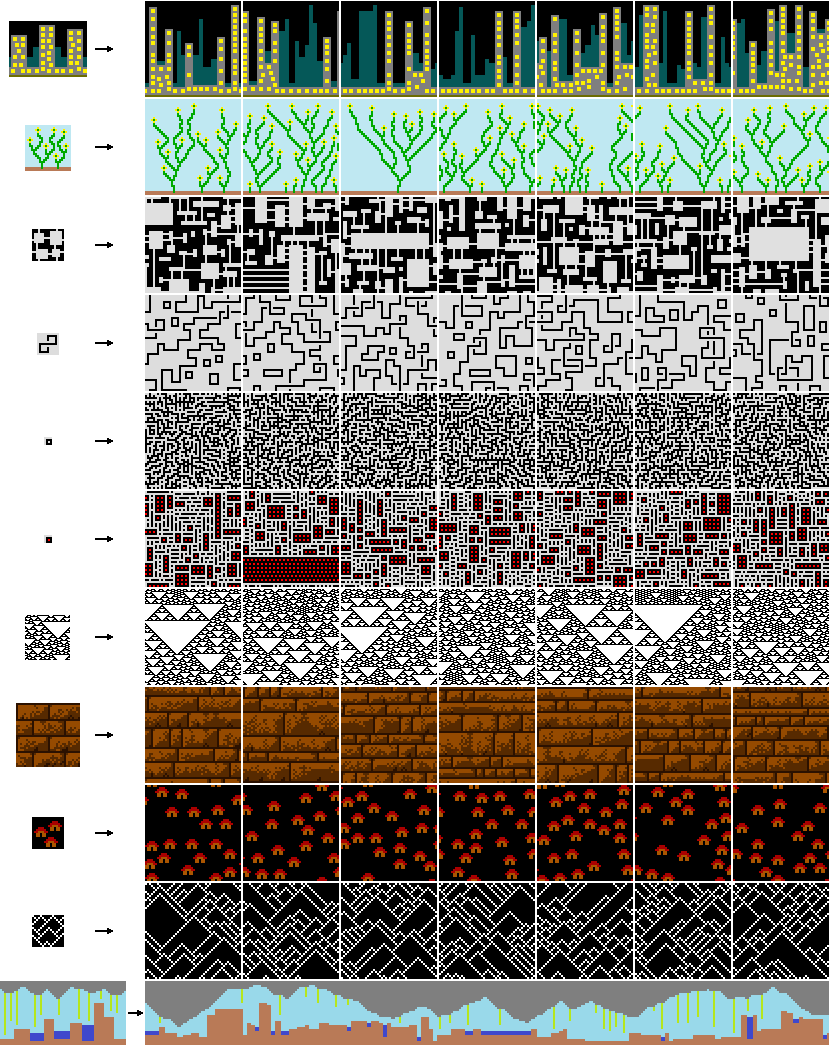

Sample pattern

Options

Generated patterns

(iteration #0 + 0000 changes)Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: